COVID-19 has unleashed unprecedented economic and social hardship as well as loss of health and lives, with responses to it, unfortunately, located in binaries of COVID and non-COVID. In the realm of public health these responses have assumed that while the former prevails, all else is marginal.

One such issue is gender based violence (GBV), which has a range of adverse physical, including sexual and reproductive health, and mental health outcomes. It has also been recognized and endorsed by member states in the 67th World Health Assembly as a public health issue necessitating healthcare and other interventions. The physical and psychological health consequences of GBV in the short as well as in the long term is experienced by one in three women at least once in their lifetimes.

Going by reports by government bodies, civil society organizations, and the media globally and in India, COVID19 and responses to it have aggravated the already enormous magnitude of GBV, earning it the moniker “shadow pandemic”. A “shadow” perhaps because it has not drawn adequate attention and response by governments despite it being a reflection of yet another long prevailing pandemic. In India, however, even the government advisories and orders with regard to essential health services continue to ignore this significant public health issue.

Conversations with grassroots organizations and activists during the lockdown in Jharkhand and Bihar, with whom Sama has been engaged, have reiterated this. An activist from Jharkhand whose grassroots organization provides support to women facing violence, explained, “We have not received that many phone calls in the past days. But this does not mean that violence is not happening as that is not possible! It only means that in the current situation of lockdown, the restrictions placed on our movement, communication, meetings, and reaching out to each other has made it difficult for women and girls who are facing violence to talk about it or come out to seek help. Right now, the only mode of communication is the phone. But many women do not have access to a personal mobile phone, as these are owned and controlled largely by the men and other family members. Women in such situation would not be able to make even a call for help. Many women while in their in-laws houses do not have easy access to mobile phones, or even a safe space to make such a phone call. It would be very challenging for those women to call and tell us about any violence that they may be experiencing.”

Cognizant of these restrictions and control, organizations had been over many years implementing strategies such as creation of safe spaces through meetings in the communities, immediate response through intervention at the location of violence and referrals and facilitation of transportation to assist women out of situations of violence.

Another woman leader of an organization in Jharkhand shared that she along with fellow activists generally organized meetings in the villages, coordinated support for women experiencing violence in homes and communities with the support of panchayat members, police, etc. These spaces were perceived as safe to share their experience of violence or seek support and even discuss and develop safety action plans. However, the lockdown has prevented systems and responses created through several years of painstaking efforts to support survivors. The past weeks of COVID 19 lockdown have diminished these strategies and instead reinforced fear, distress and violence against women and girls, and heightened power hierarchies within families, communities and other institutions.

“I got a call from a woman in my village seeking support. The woman called to seek help as she had been beaten very badly by her husband. I could only advise her over the phone to go to her parents’ house to escape from the husband. I could not go out to meet her. She had already called in help from her maternal family, so someone came from there and she left with them on a motorcycle. Her parents’ place, fortunately, was located nearby so she was able to go. I also counseled her to stop on their way by the hospital to seek medical care for her injuries”. The increased vulnerability and limited access to support and to movement due to suspension of transport and norms of physical distancing, closure of work and other social spaces have predictably led to barriers for those who want to move out of situations of violence. It has also created a challenging situation for support persons, protection officers, and/or local organizations, agencies, etc., preventing them from providing necessary services.

An experienced activist from Bihar, working on women and girls rights for many years now shared her concerns about the possibility of rising violence against women in the community. “With many migrants coming back to the villages now, loss of employment, livelihoods and increasing poverty is likely to cause distress within families and households, which are often situations that precipitate violence against women and girls. There is so much distress and crisis now in the community that in the coming days and weeks, violence against women and girls and other forms of crime will increase. Unemployment, hunger, and inequalities are deepening”.

Support systems for survivors are imperative; however, in the absence of adequate social security measures by the State to minimize the overwhelming social and economic distress, access to resources has gendered implications and are disproportionately borne by the women and girls especially from the marginalized communities. Women’s limited access to paid work, economic resources, for example, determines their access to healthcare, transport, etc.

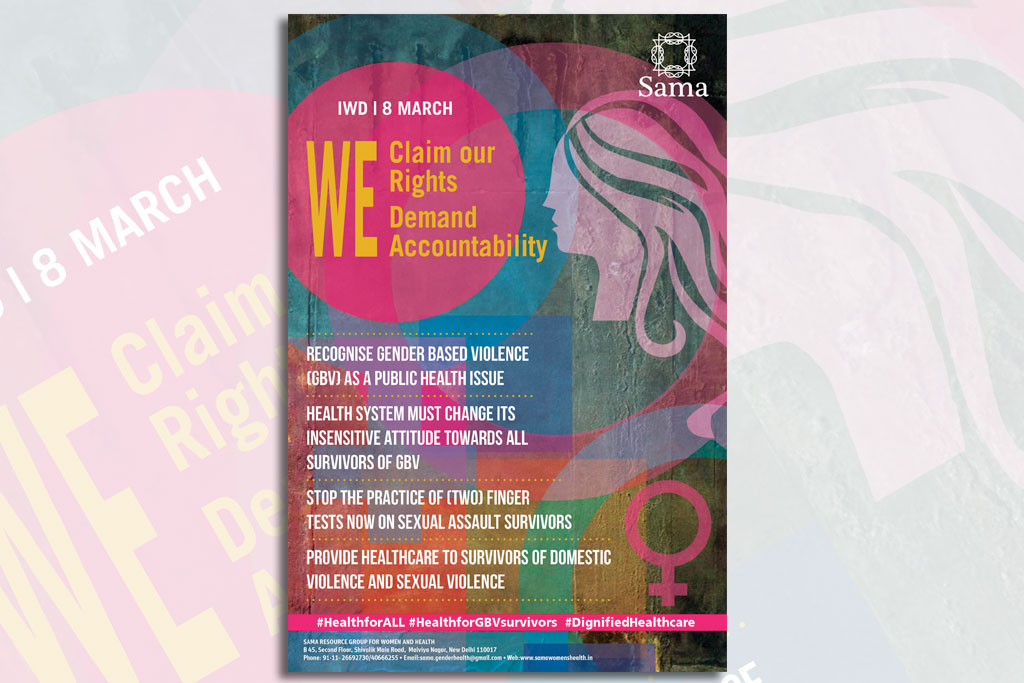

There is an urgent need to recognize GBV as a public health issue and ensure that essential services including access to ambulances, helplines as well as coordinated response teams are made available to reach survivors and provide necessary healthcare and psychosocial support as proximal to them as possible.

Moreover, while several reports reflect the increase in domestic violence, girls and women especially from marginalized communities, are also experiencing violence in public spaces. Be it the migrant woman worker who experienced sexual assault in a hospital in Bihar, the woman who faced violence in a quarantine centre in Rajasthan, or women who continue to face violence in healthcare settings in many parts of the country, gender based violence remains an extremely critical concern that must be immediately responded to. Reports indicate that the police is even more unsympathetic and resistant to registering or acting on complaints. The safety and security of women in shelters, isolation wards or institutional quarantines needs serious attention, with a recent report of rape in one isolation ward highlighting this.

Given the wide ranging health consequences of GBV, survivors’ access to healthcare providers and to treatment is imperative, including medical emergency care in extreme situations. The vulnerability of survivors necessitates a pro-active role of health systems, and governments to ensure timely, appropriate responses, including mitigating circumstances such as the lockdowns that India has witnessed, which is contributing directly to escalation of violence.