Vatsala

Short Course on GBV – 6th to 10th January 2025

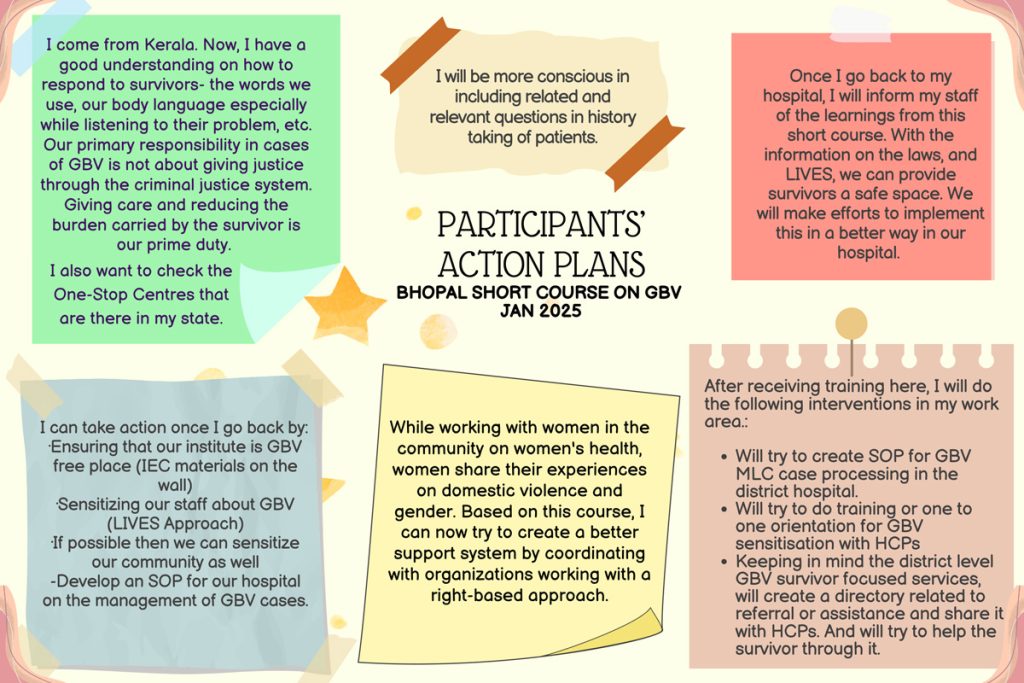

We began this new year (2025) with organising a Short Course for healthcare providers on ‘Addressing Gender-based Violence as a Public Health Issue’. This was organised as a residential programme in Bhopal from January 6th to 10th in which 15 participants joined us from 10 different states. This marks a significant milestone in our efforts, as Sama has dedicated more than a decade and a half to advancing the recognition of gender-based violence (GBV) as a critical public health issue. Short courses like these not only enhance understanding, skills, and readiness to respond to GBV but also help create a network of allies in social settings, particularly within healthcare settings. These participants become important voices for change, leadership and awareness in the ongoing struggle against GBV.

Conversations about gender-based violence (GBV) often face challenges due to the limited ways in which this issue is perceived. For a long time, we have struggled with viewing domestic violence or any form of GBV as a “private issue.” This perspective, as we all know, has led to the normalisation of GBV, resulting in survivors being left without emotional support or assistance upon disclosing their experiences. Additionally, society tends to react only to extreme instances of assault, focusing on punishing those responsible for a single incident rather than committing to broader change in patriarchal gender norms. Furthermore, GBV is frequently viewed solely as a legal or criminal justice issue, which overlooks the significant impacts it has on the health and well-being of survivors. The extent of this impact necessitates a comprehensive public health response.

Given this background, some of the core points that this short course was set out to address were:

- GBV’s health consequences and impacts on the well-being and the lives of those affected and vulnerable to violence

- Healthcare system as an immediate and safer space for survivors to disclose violence and seek support. Healthcare providers are often among survivors’ first points of contact and can be important in linking survivors to other support systems.

- First-line support is crucial to ensuring the health and well-being of survivors.

- The health system has a legal and ethical obligation to respond to GBV and there is a need to cultivate willingness amongst the healthcare providers for playing this role

These short courses and training programmes enable the creation of a feminist space and pedagogy of reflection, perspective building, and knowledge exchange and discussing real-life scenarios, case studies, etc., that not only enhances the skills and preparedness of the participants as healthcare providers and frontline workers at the community support systems-but also promoted the recognition of gender rights and reproductive justice-within the discourses around responding to GBV in a caring, affirmative and health and well-being centred manner.

This facilitation is effective because it discusses gender through the lenses of intersectionality and marginality. Participants appreciate this approach as it broadens their understanding of gender and deepens their awareness of it as a social, structural, and systemic issue. The effectiveness of this facilitation is enhanced by the involvement of rights-based practitioners who work at the grassroots level in various social contexts. When these practitioners interact with participants and share their experiences—whether related to trans communities, queer rights, or the struggles of sex workers against health system prejudices—it opens up numerous opportunities for learning, sensitisation, awareness, and solidarity.

For example, in this Bhopal short course, we had Ajay ji (Samvedna), who amplified voices of the marginalisation based on sex work and caste hierarchy in Madhya Pradesh. He skilfully pushed the understanding of the participants to view the boundaries of their own reflections on who still gets excluded and how, from such thinking and conversations about improving our approach or eliminating GBV.

Through connecting with the Ektara Collective, we organised a screening of the film “Ek Jagah Apni,” which was followed by a moderated panel discussion featuring the filmmakers and actors. This deepened our exploration of intersectionality, as the film portrays the experiences of two trans women navigating their everyday lives in Bhopal. It highlights their struggles with housing issues, as well as the violence and discrimination they face at various levels, often hidden in the shadows of urban spaces.

Additionally, and more importantly, the film emphasised the significance of subtle acts of support. This is especially important because, in my conversations and discussions, I have noticed a strong focus on the lack of law and policy implementation as the main barrier to creating violence-free spaces. While the failure of implementation is indeed a critical issue, we also recognised the need for simultaneous and parallel changes in the environments we inhabit. Although structural change is essential for addressing gender inequality, it is important to acknowledge that systems are composed of people, and people, in turn, embody these systems at times.

In a prior session, Adsa (Sama team member) encouraged participants to collaboratively develop a working definition of gender-based violence (GBV). During this process, she prompted us to critically examine our definitions and consider whether we view GBV primarily as an outcome of broader societal issues or as a root cause that influences various forms of discrimination and harm. This thought-provoking exercise not only complemented our ongoing discussions about gender dynamics and power structures but also shifted our perspective. We moved beyond the role of passive participants in a short course on GBV to becoming active agents capable of perpetuating or challenging instances of violence in our communities. Through this reflective process, we gained a deeper understanding of the complex and often hidden manifestations of violence, enabling us to visualise and address issues that might otherwise remain overlooked and unchallenged.

In the subsequent days of the short course, Madhu (Ektara Collective), along with Muskan (one of the Ek Jagah Apni film’s protagonists), and Suraj (C-Help)—joined us as panel speakers. Moving beyond the film, they shared their experiences and stories from their own lives, which deeply influenced their work. They also emphasised the urgent need for solidarity, especially in these challenging times when anti-rights narratives are increasingly shaping our realities. Muskan delved into the complexities of gender marginalisation, helping participants explore the nuances of gender identities. Additionally, Suraj highlighted a crucial point: while identities can help recognise and validate marginalisation, they can also become a tool of control.

Building on these dynamic discussions, Kushi (Enfold Proactive Health Trust) and Sanjida (Cehat) further enriched the session by providing participants with insights into various GBV-related laws and strategies for navigating legal and institutional systems. The understanding of GBV as a public health issue got reiterated, along with discussions on how the health system responds to GBV and what best practices in healthcare settings can look or appear like.

Each session built upon the previous one, shedding light on the connections between issues that are often viewed as separate. My hope for courses like this is to establish gender and intersectionality as foundational perspectives. This approach aims to help participants not only understand but also critically examine interventions, guidelines, and policies related to gender-based violence (GBV). A deeper understanding fosters context-specific applications and opens the door to developing interventions that surpass existing standards, all while sharing current knowledge and best practices.

Vatsala acknowledges and thanks Adsa for her inputs and guidance on this piece.